Here Comes the Bride

I am not a goth. It’s a common misunderstanding, seeing as how ninjas wear black too.

I am not a goth. It’s a common misunderstanding, seeing as how ninjas wear black too.

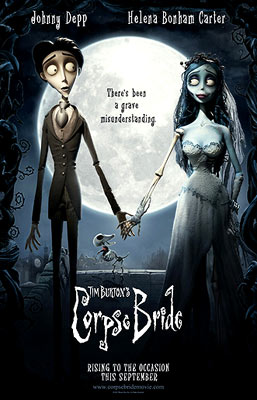

That being said, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride is a must-see.

Tim Burton’s movies touch a very universal chord of sentiment in a way that many filmmakers cannot. It’s a shame that the Goth culture has embraced his work as an expression of their angst: the irony is that Goths identify solely with Burton’s isolated characters whereas Burton clearly makes his movies with no niche in mind. His films are not elitist nor categorically defined, which is perhaps why there are so appealing.

Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride has been compared to being direct kin to The Nightmare Before Christmas, but the relationship is merely superficial. This film has more in common with his masterpiece, Edward Scissorhands: it is a fairly simple love story wrapped under a Gorley-esque gothic bow. Better said, it combines what was good about its predecessors and amalgamates it into one of this year’s best films.

The appeal of Burton’s work here and with Edward Scissorhands is that the emotional stakes are raised by the impending permanence and finality that their climaxes entail. Romantic movies follow a generic formula of one sex seeking the love of another (the end, as in real life, is either positive or negative and rarely inbetween). Realistically, however, there is very little at stake: the jilted lover will continue his or her life in pursuit while the lovebirds will find complications within their relationships. There is no finality to the romantic movie taken to its logical conclusion. But Burton’s characters are not afforded such a luxury. They are separated from the world in such a way that they are not afforded a second chance. Edward Scissorhands will either get the girl or be secluded from the world: there will, literally, never be another girl. It is perhaps this, and not the gothic imagery that Burton utilizes, that appeals to the Goth subculture: an overwhelming yet temporary anxiety that unrequited love will be a permanent facet of life.

In both films discussed, the protagonists are not given the happy ending but instead learn to appreciate and live a true and lasting definition of love and life. Edward will forever be stuck in his mansion for eternity, caught in a freeze-frame of having loved and lost yet forever more at peace. At the end of Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, one of its protagonists must also peacefully contend with the reality of the situation. What makes these moments that much more meaningful is that they are essentially the opposite of what we are taught about practical love: we respond to rejection with anger, contempt, and a passive attitude that is accusatory and/ or apathetic. We aim to move on. Burton’s characters are uplifting in that they encourage an idealistic view that love and hope should exist beyond hurt and pain, both of which are temporary.

“Always the bridesmaid, never the bride” is how one character describes the afforementioned Corpse Bride. Unlike movies which attempt to disprove or rise above such negative sentiments, the characters of Tim Burton accept the grim reality of their situation and are content with their lot in life.

Grade: A